In the Shadow of the Mother: The Politics of Family in Maeve Brennan’s “The Visitor”

by Molly Frank

Photo by Lucas Swinden

Families and communities are often viewed as microcosms of society. This is particularly prudent for stories written during or in the aftermath of a large cultural shift. Irish writer Maeve Brennan, born shortly before the 1921 Anglo-Irish Treaty, grew up in the shadows of the Irish independence movement and the creation of the Irish Free State. Although the exact date The Visitor was written remains unknown beyond the early 1940s, it was written shortly after the 1937 Constitution that reaffirmed the idea that Irish women belonged in the home. The Visitor illustrates, through the relationships between mothers and their children, that domestic life is suffocating, not just for women, but for their children.

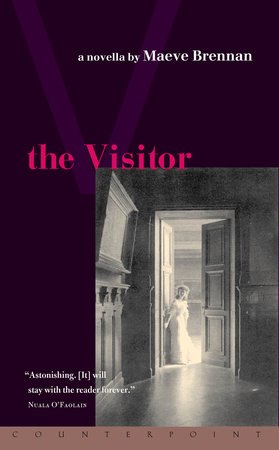

The Visitor by Maeve Brennan,

Counterpoint, 2001.

After the 1921 Anglo-Irish Treaty, the Irish Free State was formed alongside the partition of Ireland. The Treaty was politically divisive from the start. It would not be until 1937 that some of the political turmoil would cool down with the election of an anti-Treaty government that would immediately begin to define Irish identity (Daly 99). The most obvious of these attempts would be the creation of the 1937 Constitution. Although such political documents are often looked at as neutral documents, they often have a fictitious element to them. As Barry Collins and Patrick Hanafin describe, “it is necessary to place it in not just [a] historical context, but also in a theoretical context which addresses the sense in which constitutionalism attempts to ground its own legitimacy in the narration of a new political imagery” (54). Collins and Hanafin address the fictionalizing of identity within a country’s constitution. This is not a malicious act, but one that every constitution engages in. Constitutions are given such weight to define the future of a nation that it is only natural for them to contain hopes of the nation and the ideal citizen.

Collins and Hanafin argue that the Constitution embodied a “mythic narrative” of a “rural idyll” housing an “untroubled, rural small-holder” (56). These images evoke a sense of traditionalism that did not represent the urban life of Ireland. Such documents are an attempt to harness nationalism to create a national identity by the political elite (Collins & Hanafin 58). By doing so, the government can create a rallying point for the country to gather around and forge a new way forward. While men are embodied as these rural farmers and cultural practitioners, women are relegated to a domestic role (Collins & Hanafin 56).

After the war, the government enacted several conservative laws and acts limiting women’s political and public roles before finally codifying them in the 1937 Constitution (Valiulis 118–19). Valiulis writes, “By 1937, women’s political, economic, and reproductive rights had been so severely curtailed that women were explicitly barred from claiming for themselves a public identity” (120). This was all due to Article 41.2 of the Constitution that pledged mothers would not have work to the neglect of their home (O’Connor 179). Pat O’Connor specifically notes that in the article, the words “mother” and “woman” are used interchangeably, binding women legally to the role of mother in society (180). Although legal prospects were certainly significant, no less so would be the expectations these women would have faced. Under this Constitution, Collins and Hanafin write that women become a “representation of the nation” where they are deified as “mother” or “virgin” (55). With this idea, every action becomes a representation of the nation. So, when a woman acts out, she is not just shaming herself or her family but actively betraying the nation.

The Visitor revolves around the young Anastasia King returning to Dublin from Paris after the death of her mother who ran away from her husband six years prior (Brennan). Throughout the story, Brennan writes about many different familial relationships that have great impact on Anastasia and the King family. The story particularly focuses on four parent-child/grandparent-grandchild relationships that revolve around isolationism and the destruction of the family. Angie Henderson, Sandra Harmon, and Harmony Newman write that families “exist in two spheres, both public and private.” This necessitates the considering of the public expectation of gender roles (Henderson, et. al. 512). Although the Irish Free State seriously restricted the public role of women, there was still a public expectation on them to be perfect mothers.

The particular emphasis on Irish sons is reflected in the relationship between Mrs. King and her son, John. There are several moments that display her absolute devotion to her son and anything that disrupts that relationship becomes a threat. Mrs. King fully integrates her identity into that of her son. Her son does not marry until he is 40 years old, and Miss Kilbride tells Anastasia that it was “a great shock to [Mrs. King]” (Brennan 46). Mrs. King had never imagined her son marrying because for him to do so would disrupt her sense of identity. This is further confirmed by Mrs. King, who says, “I am his mother, and my place is with him. His place is with me. God knows I loved him more than anyone else ever loved him, my only child. He should never have married . . .” (Brennan 55). Mrs. King recounts this while describing to Anastasia that she will be buried next to her son after she dies in the traditional place a wife would be buried. It is interesting to note that Mrs. King’s husband is never mentioned, nor does she want to be buried next to him. Rather, her entire identity and love is bound to her son. David Matley reports some women experience a sense of “alienation from self” and lose their identity to the role of motherhood (3). Mrs. King certainly seems to embody this. She has no identity outside of her son and so is unable to move on when her role becomes redundant.

Mrs. King is the head of the household even after her son marries and brings another woman into the house. She is described as having sat at the head of the table, putting her in a position of authority over the family. This is further confirmed as she scolds the family over their relationships and dynamics with each other, acting out a defunct role (Brennan 10). John is married to Mary; Mrs. King should no longer be the woman of the house. Mrs. King, however, is unable to give up her role in the family. In a society where a woman’s only value and contribution is to be a mother, there is nothing for her once her child is grown. The rejection of an identity outside of the motherhood role leaves her to either be left with nothing or usurp the role from her daughter-in-law, leading to more problems within the home. She is unable to even be a grandparent because she is so focused on being a mother to her adult son that she ignores Anastasia, a memory which becomes very defining for how Anastasia views herself within the family (Brennan 10). Mrs. King’s inability to separate herself from her role of mother alienates her from her daughter-in-law and her grandchild.

Mrs. King has committed the ultimate sin in society by outliving her child. Because her role and identity are so tied to her son, she is completely isolated once he dies. She remarks to Anastasia that she sees “no one whatsoever” (Brennan 17). Although she later does invite Miss Kilbride into the house, even then she seems annoyed and distant from her (Brennan 20-23). Even after she has no one left, she effectively exiles Anastasia and cuts herself off from any remaining family she has (Brennan 75). Because motherhood is the penultimate role for a woman, once her son is dead, she has no function. Even being a grandmother cannot fulfill her. With no living sons, she is essentially waiting to die and end her family line. She intends to send Anastasia back to Paris and leave no remains of her family behind. The King family, as it exists in Dublin, will die with her because Mrs. King has no identity outside her role as a mother to her now dead son.

Her alienation of her daughter-in-law also has disastrous consequences for the relationship between Anastasia and her mother, Mary. Throughout the novella, Anastasia’s mother is only ever called by her name once in a remembered conversation between Anastasia’s father and mother (Brennan 9). Beyond this, her mother is only ever referred to as her mother, or even “the mother,” completely removing her sense of identity within the story except for as her role (Brennan 9). In a fight with Mary, Mrs. King describes Mary’s parenting and nervousness because of the way she was raised by saying, “Don’t blame her. It’s the way she was brought up” (11). This brief comment by Mrs. King becomes a foretelling for the relationship between Anastasia and her mother. The insecure attachment Mary had with her own parents, who apparently raised her to be nervous and prone to fits of emotions and scenes, comes to define Anastasia and her mother’s relationship (Brennan 9–11). Mary comes off as so emotionally frail that when Anastasia runs away to join her mother in Paris, it is clear this is because she feels responsible for caring for her mother (Brennan 33–34). Because of this cyclical attachment style, Anastasia is forced to step up into a parental role for her mother.

Anastasia’s attachment style is displayed primarily through two key scenes involving her mother that end up defining how she functions as an adult in her relationships. In the first scene, Anastasia recalls her mother walking her up to bed and then waking up an hour later to discover her mother just sitting in her room, staring out the window (Brennan 9). The second scene is the breakfast scene where Anastasia witnesses her mother and father fight and then her mother being scolded by her grandmother until she breaks down in tears, convinced that Mrs. King is trying to break up the relationship between Anastasia and Mary (Brennan 9–10). Both scenes portray Mary as the depressed mother and the victim of her husband’s and mother-in-law’s hostility. Anastasia’s relationship in the family dynamic becomes tied to her mother, the only person who tries to care for her emotionally. This defines how she approaches her grandmother who she views as the villain that drove her mother away and never approved of her. This also affects how Mrs. King views Anastasia, who she sees as an extension of her father. Because Mrs. King views Anastasia’s mother as an interloper in the family, Anastasia’s choice to take care of her mother is the ultimate betrayal. In a society that values the primacy of the son, Anastasia desiring to care for her mother is inexcusable.

The nervous attachment style between Anastasia and her mother also hurts Anastasia’s ability to form other relationships. Although Anastasia says she has friends, she recalls not being overly close to anyone and not seeing them outside of class. In fact, after her first year, she does not even return to class and devotes all her time to caring for her mother (Brennan 34). Anastasia takes on a twisted version of the mother’s role and, like Mrs. King, becomes so entwined around her relationship caring for her mother that she is unable to form any other attachments. Her entire role is defined by her caretaking and, thus, when her mother dies, she has no other role left. Even after her mother dies, she is still taking care of her. She believes she sees her mother following her and decides to “leave” her in a church for safety and fights with her grandmother to have her mother’s body brought back to Dublin, which was her mother’s last request (Brennan 27, 55). Her inability to form stable attachments causes her to throw away Miss Kilbride’s ring, symbolically ridding herself and Miss Kilbride of any attachments they had in life or in death (Brennan 72). By throwing away the ring, Anastasia rids herself of her attachment to Miss Kilbride, her mother’s friend who, perhaps like Mrs. King with Mary, Anastasia may view as an encroachment on her relationship with her mother. Anastasia rids Miss Kilbride of her desired attachment to her lost lover. By the end of the novella, Anastasia appears to have a mental breakdown. Looking to shame Katherine and Mrs. King for throwing her out of the house, she takes off her shoes, walks out into the middle of the street, and begins singing outside their window (Brennan 79–80). Beyond being bizarre behavior, it is also self-destructive. The final words of the novella are of Anastasia calling out goodbye and saying she had not left yet (Brennan 80). The ambiguous ending seems to allude that Anastasia could potentially be committing suicide. Regardless of whether she lives or not, Anastasia has effectively declared the end of the King line.

The final parental relationship is between Miss Kilbride and her mother. Although their relationship is mainly viewed through Mrs. King’s words, it provides a startling reflection of the other relationships. Miss Kilbride’s mother is described by Mrs. King as a “demon” who “ruled” her house with “an iron rod.” Mrs. King notes that she prevented Miss Kilbride from getting married and even after death “still has [Miss Kilbride] under her thumb” (Brennan 27). Even Miss Kilbride, although very fond of her mother, still describes her in a way that makes it clear how unhealthily attached they were. She tells Anastasia that her mother used to refer to her as her “other self” once again displaying that conflation of mother, child, and identity (Brennan 39). Like Mrs. King, Mrs. Kilbride was completely attached to her daughter and viewed the act of getting married as a threat to her own role and identity in her daughter’s life. This was likely confounded by Mrs. Kilbride’s own disability and reliance on Miss Kilbride for care (Brennan 25). Like Anastasia, Miss Kilbride fulfilled the twisted role of mother to her own mother. Thus, the two’s (Mrs. and Miss Kilbride’s) identities became completely wrapped around each other. This ultimately culminates in Miss Kilbride dying alone and single, with no children to pass her legacy onto. Miss Kilbride, as the ultimate conglomeration of both Mrs. King and Anastasia, shows what happens when one’s identity is completely determined by motherhood. She represents a warning to Mrs. King and Anastasia that they fail to recognize and comprehend by the end of the novella, leading to them presumably following the same path in the future and destroying their family.

Although Maeve Brennan was purported to have steered clear of politics in her writing, her narratives serve as warnings (Bourke). Thus, Brennan’s stories may not be directly political, but her use of storytelling and personal narratives construct an understanding of the society she was growing up in. Maeve Brennan understood the threat of confining women to the identity of “mother.” The Visitor warns readers that women who have no purpose or identity outside of their family will eventually lead to the destruction of family and, in the grand scale, the breakdown of society.

-

Bourke, Angela. “Brennan, Maeve” Dictionary of Irish Biography, revised 2021, 2009, https://doi.org/10.3318/dib.000928.v1.

Brennan, Maeve. The Visitor. Counterpoint, 2000, Washington D.C.

Collins, Barry, & Patrick Hanafin. “Mothers, Maidens and the Myth of Origins in the Irish Constitutions”. Law and Critique, vol. 12, 2001, pp. 53–73.

Daly, Mary E. “Women in the Irish Free State, 1922–1939: The Interaction Between Economics and Ideology”. Journal of Women’s History, vol. 6, no. 4, 1995, pp. 99–116.

Harmon, Sandra, et al. “The Price Mother Pay, Even When They Are Not Buying It: Mental Health Consequences of Idealized Motherhood”. Sex Roles, vol. 74, 2016, pp. 512–26.

“Irish War of Independence”. National Army Museum, https://www.nam.ac.uk/explore/irish-war-independence.

Matley, David. “‘I miss my old life’: Regretting motherhood on Mumsnet”. Discourse, Context & Media, vol. 37, 2020, pp. 1–8.

O’Connor, Pat. “Defining Irish Women: Dominant Discourses and Sites of Resistance”. Éire-Ireland, vol. 30, no. 3, 1995, pp. 177–87.

Valiulis, Maryann Gialanella. “Power, Gender, and Identity in the Irish Free State”. Journal of Women’s History, vol. 6, no. 4, 1995, pp. 117–36.

Molly Frank is a writer and scholar from Northeast Ohio. In her scholarly work she examines issues of feminism, global politics, and identity in speculative fiction. Through her creative work, she is drawn to themes of relationships between women, including romantic, platonic, and familial, cycles of history, and a sense of physical and metaphorical belonging. She has an MA in Literary Studies from Queen's University Belfast and a BA in English Literature from Westminster College. She is currently pursuing a PhD in English Screen Studies at Oklahoma State University. When not buried in stacks of dusty books or hunched over a computer screen, Molly can be found outside, grounding herself with the literal ground.