Bread & Butter

by Livia Meneghin

On January 13, 2025, I emailed poet friends of mine with an invitation to community and writing. At the time, I was feeling completely out of control when it came to my place in the world, literary or otherwise. This feeling was pervasive in my life; I was baffled by people and institutions okay with complicity in genocide, panicked over climate catastrophe, and stuck in a consumeristic system. I was scouring for manuscript contests or residency applications with fee waivers, only to be rejected months later time and again, unable to secure a full-time teaching position to support my family despite having a terminal degree and spending more time focusing on getting published than actually writing poetry. Furthermore, I was not alone in these experiences.

“Poetry is Not a Luxury” from Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches by Audre Lorde.

Crossing Press, 1984.

When artists feel powerless, like their creativity and poetry is not enough (for themselves or for any real change), it is not the fault of the artist; it is by the design of capitalism, colonialism, and patriarchy. In her essay “Poetry Is Not a Luxury,” Audre Lorde tells us, “For within structures defined by profit, by linear power, by institutional dehumanization, our feelings were not meant to survive.” Therefore, in order to decolonize our relationship with writing and publishing, to re-empower ourselves by shifting our focus, and take everyone we can along for the ride, we must look in a different direction than perpetuating the status quo. We can feed multiple birds with one scone by learning a new craft and feeling the joy of bringing people together by giving something back. And so I did.

Bread & Butter Press (B&B) isn’t a literary press in a conventional sense. It is more of a poetic gift economy. For its first iteration, completed in May 2025, B&B consisted of handmade and handbound poetry anthologies, typed via typewriter and featuring collected offerings of poetry. This process does not involve “submission,” which, according to Merriam-Webster, can also mean “the condition of being submissive, humble, or compliant” or “an act of submitting to the authority or control of another.” There was no money involved either—the invited poets did not need to pay a fee, nor were they paid. All contributors, that is, those who gifted their poetry within a designated time frame (one I was flexible with in extenuating circumstances) received a gift in return: a free copy personalized with a unique collage from magazine scraps and their name written on the back cover. I did accept financial assistance with postage for those not residing on Massachusett Tribal Lands or within driving distance, but this was not a requirement. The supplies needed to bring B&B to life were harvested from my current stores: thread from my grandmother’s old sewing box, construction paper from my place of work, collage materials from my crafting drawer, and, of course, my typewriter, which was a birthday gift from a few years back.

B&B was named for my grandmother, Gilda, who often went by Jill and, for much of her life, Nanny. Gilda grew up during the Great Depression and loved bread and butter as a dessert or small meal. She'd always describe it as delicious, nutritious, and all she could really need. These qualities are what I envisioned my anthologies would bring, both to contributors and to myself. In my invitation I wrote: “I admire you & your poetry dearly, & would love to hold a book with your words in it for my birthday.” The first edition of B&B kickstarted in January 2025 and finished in time for June 5, 2025, with time to spare.

For its first iteration, completed in May 2025, B&B consisted of handmade and handbound poetry anthologies, typed via typewriter and featuring collected offerings of poetry.

With B&B, I dedicated hours towards being creative, connecting with people, and using my hands instead of being on the computer. Typing on a typewriter is a unique experience fewer and fewer people know. And while I’m no pro, mostly using my index fingers and needing to really hammer down each key in order to get the ribbon ink stamped dark enough onto the paper, it is a very satisfying movement. The clanking and dinging sounds, even the way the machine would almost reverberate on the table so much that I would need to constantly pull it back in place directly in front of me. Collaging for B&B similarly required hand-eye coordination and attention. I flipped through magazines, such as vintage National Geographics, and used scissors or gentle tearing to make the shapes and colors I felt a particular poet would enjoy. Audrey, for instance, often writes humor into her poems, and overall is someone I find cheerful. For her collage, I arranged a llama to be saying “Bread & Butter.”

Sewing the book was just as relaxing as the above earlier two steps in the process. My partner helped me with this part, too, which was another delightful form of connection and quality time spent with a loved one. We watched a brief YouTube video called “How to Bind Single Section Booklets (beginner friendly stitch patterns!)” by user Sea Lemon and picked our favorite stitches. Mine ended up being something of a dash stitch, and though it wasn’t always perfect, perfection was never the goal.

Sewing the book was just as relaxing as the above earlier two steps in the process…though it wasn’t always perfect, perfection was never the goal.

The specific call was for the poets to respond to the question: “How do you feel relief/safety?” I chose this question because as humans, our attention economy was, and still is, in danger. So much of societal expectations and systems, including patriarchy, colonialism, and capitalism, place all people (especially marginalized people) in a scarcity mindset. We are told we don’t have enough and need more because that will get us to keep showing up for work every day, to keep purchasing fashion products and entertainment, and to continue thinking we can only exist in survival mode. By offering a space for them to consider where they have enough, feel relief and rest, and experience safety, poets are better able to combat these larger forces in a small way.

B&B was also the work of breaking the publishing cycles of agency—or should I say lack of agency—within the submitting process. Too often poets are put in the vulnerable position of being backed into a corner, of being made to feel desperate to be published. Due to their own time, budgeting, and capabilities, editors in poetry publishing often do actively engage with the time, effort, and humanity behind each submission; some don’t do this out of wrongfulness or cruelty, but even with good intentions, coming back to a poet with with a few notes of “cut this” or “change this”—if providing any notes at all, rejection or acceptance—doesn’t do anything to build a relationship between editor and poet.

For B&B, I requested one to three offerings of shorter poetry due to the fact that I would be using half of an 8.5” × 11” paper per page. I most often welcomed the poetry as shared, selecting one to include in B&B. In a few cases, I started a conversation grounded in curiosity, questions, and collaboration, not in asserting what I thought was better for a poem. I did not send standard “edits.” This project wasn't about earning approval, “submitting,” or straying from authenticity; instead it was about reaching the end of a road together with something to be proud of and excited by. Similarly, I wrote in my invite that previously published/simultaneous submissions didn’t matter to me. People could send me work already published, new, old, under consideration elsewhere. B&B would not have an ISBN, nor would it really be a publication at all; instead B&B more closely fits in the category of a gathering, an avenue for joy and connection.

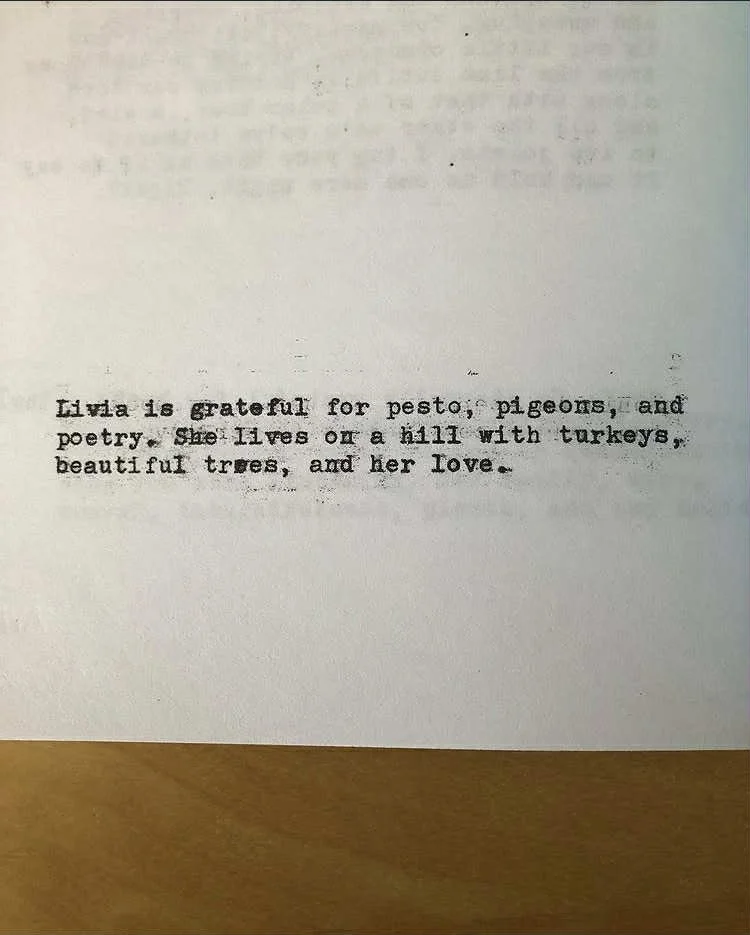

Another feature of B&B that differs from what is standard, or should I say normalized, within publishing is the author bio. In my email, I asked for a short (1–2 sentence) bio featuring what poets are grateful for and/or honoring where they are in space by referencing flora, fauna, or a Native Ancestral Land acknowledgment. Not surprisingly, it was seemingly hard for folks to break the habit of what more typical writerly bios seen across the publishing world look like. It is routine to include accomplishments and acknowledgment of expertise, such as a secondary degree and from what reputable institution. My ask was a way of shifting perspective, of considering what we already have as worth sharing with others, rather than only focusing on seeming the most competitive or impressive as a way to stand out amongst others. In other words, I wanted to know, for example, that Mary “lives in a yellow house in front of a stand of Red Pines, not far from a wildlife refuge, which is where she goes to build driftwood forts with her kids and hopes to get a glimpse of a snowy owl.” That information tells me more about her and speaks to the abundance in her life just as much as, or in some ways more than, her occupation, awards, and previous publications. Such a bio is more human, and poetry is all about connection, humanity, and freedom to live outside of constraints.

My ask was a way of shifting perspective, of considering what we already have as worth sharing with others, rather than only focusing on seeming the most competitive or impressive as a way to stand out amongst others.

B&B was an experiment, a gift, an engagement with my physical world and with my people. I have since been reflecting on other ways I can challenge publishing norms and encourage poets to be human first in a world that asks us, more and more, to hand over basic thinking, observing, and writing skills to technology, not to mention ways I can improve my participation in my community as a poet and activist. Reading this, you may feel compelled to ask: How can B&B exist on a larger scale? I gently answer that this is somewhat the wrong question, or framed in a way that still sees endless growth as an end goal. Still sees the only way something can be valuable is if it’s forever, if it is large. How can more B&Bs exist, is my offering as a revision. How can more poets, artists, and editors invent ways to dream within our world? How can we reach out to each other more intentionally, inclusively, and kindly? I say, start by sitting down with a slice of bread and butter, enjoy your snack, and then get going.

Livia Meneghin (she/her) is the author of feathering and Honey in My Hair. She is Cofounder and Managing Editor at Two Cardinals Literary. At Sundress Publications, she serves as Assistant Chapbook Editor and Reads Editor. Livia has been awarded recognition from the Academy of American Poets, Breakwater Review, The Room Magazine, the City of Boston, and elsewhere. Her writing has found homes in Colorado Review, CV2, Gasher, Honey Literary, The Journal, Osmosis, and Thrush, among others. Since earning her MFA in poetry, she teaches writing and literature at the collegiate level. She is a cancer survivor.