Scary Poppins

by Sofia Grady

Image from Jay Mistry

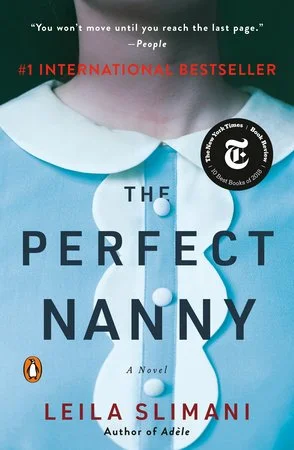

The Perfect Nanny, written by French-Moroccan writer and journalist Leïla Slimani, fictionalizes the notorious murder of Leo and Lucia Krim by their nanny, Yoselyn Ortega, on the Upper West Side of Manhattan in 2012. Slimani shifts this tragedy to a small apartment in the tenth arrondissement of Paris, France, where the Masses family resides. Paul and Myriam are parents to two young children, Mila and Adam, who require a nanny when Myriam decides to return to her career as a full-time lawyer following Adam’s infancy. The work left me reeling. The dissonance between Louise’s silent violence and perceived love for the children mimics the dynamics in abusive relationships and echoed the hauntings of my own experiences.

The Perfect Nanny by Leïla Silmani, translated by Sam Taylor.

Penguin Books, 2018.

After several failed interviews, the couple hires Louise, a seemingly perfect, doll-like blonde who is endlessly patient and exceptionally clean. The new nanny appears to be a miracle—she never tires of the children’s imaginary games, there is never a single dirty dish in the sink, anything that needs doing, has already been done tenfold by the time Myriam and Paul return home from work in the evenings. Then slowly, we watch as the nanny declines into a madness so overwhelming that it drives her to murder the two children, and then herself, with a kitchen knife before bath time.

The novel’s opening line—“the baby is dead”—immediately divulges the ending to this fairy-tale-gone-wrong. However, Slimani never actually provides her reader with the violence that the story’s climax is perched upon. Instead, she spends 228 pages hinting at the true evil that lies just beneath the surface. Reading this psychological novel feels a lot like holding your breath. In it, there is an ever-present sense of evil and violence; a presence that would be minimized if the violent climax was actually depicted. In her withholding, Slimani expertly disconnects the known and the suggested, allowing her abundant foreshadowing to fill in the space that she leaves.

It’s peculiar to consider foreshadowing in a novel where the ending has already been spoiled, yet Slimani does it with ease. Rather than operate like a traditional mystery, where the who is the subject of the reader’s focus, The Perfect Nanny gives the reader the who, and asks them to consider the why. This foreshadowing begins immediately; as early as page 14, Slimani writes,

Ever since her children were born, Myriam has been scared of everything. Above all, she is scared that they will die. She never talks about this—not to her friends, not to Paul—but she is sure that everyone has had the same thoughts. She is certain that, like her, they have watched their child sleep and wondered how they would feel if that little body were a corpse, if those eyes were closed forever.

While this is a rather normal parental concern, it is a haunting passage when immediately prior, the reader has learned that this mother’s fear does, in fact, become a reality. This horror builds as the reader moves through the book and continues to follow the breadcrumbs that inevitably lead to the children’s brutal end. Louise’s takeover of Myriam’s family is slow, but intense. And despite Myriam’s initial fear that her children will die, she does nothing as we watch the nanny’s mental wellness decline, taking the children with her.

Later, when discussing a fight between Myriam and Paul’s mother, Sylvie, Slimani writes, “That night, she felt as if she were being assaulted, thrown to the ground and stabbed repeatedly with a dagger” (127). This further foreshadowing of Myriam’s concern with death specifically depicts how her children are killed at the story’s climax. At the novel’s peak, Slimani returns to this foundational fear of Myriam’s. “All night long, Myriam thinks about that carcass on the kitchen table. As soon as she shuts her eyes, she imagines the animal’s skeleton, right there, next to her, in her bed” (169). The image of carcasses in bed with Myriam is a direct foreshadowing of Myriam finding her children dead in their bedroom, where we begin the novel. Rather than including the violence of the actual final act, Slimani sprinkles it throughout the novel in other, suggestive ways. The skilled author decides, when considering her craft, to spread this sense of evil throughout the entirety of her story, rather than build it into one final violent scene.

The title of the novel itself, The Perfect Nanny, suggests that this may be a story about quite the opposite. When Louise is first introduced to the family, Slimani writes, “she appears imperturbable. She looks like a woman able to understand and forgive everything” (19). Of course, the “perfect” anything does not exist, and no human is truly immune to a range of emotions. This image that Slimani builds for us of Louise works as a jilting juxtaposition to what we already know about this nanny before we have even learned her name—that she kills the children. This façade of doll-like perfection that surrounds Louise early on in the novel serves as foreshadowing to something much darker within her.

Louise’s early presence in the house feels almost magical. There is a sense of fairy tale in the perceived perfection of Louise’s work. Though Slimani explains, as she does with most everything throughout the novel, that evil is always lurking.

Where do these stories come from? They emanate from Louise, in a continual flood, without her even thinking about it, without her making the slightest effort of memory or imagination. But in what black lake, in what deep forest has she found these cruel tales where the heroes die at the end, after first saving the world? (30–31)

Slimani takes every chance she can to warn her readers what lies ahead. In everything that Louise does, Slimani reminds us of what we already know is coming. This conflict that she creates between what we know, and what she suggests to us through her foreshadowing builds a palpable tension in this novel as you read.

This perfection that follows Louise early on serves as a means to gain control over the house, the children, and the family. She interweaves herself so deeply into their lives that they cannot do without her, she becomes the mother to all four individuals. She makes them her own. “She feels a serene contentment when—with Adam asleep and Mila at school—she can sit down and contemplate her task. The silent apartment is completely under her power, like an enemy begging for forgiveness” (27). Early on, we see Louise’s interactions with others as meek and submissive, although Slimani hints that such power dynamics may not be as they seem. As the novel progresses, Louise slowly starts to gain more and more control over the house and the children, and this early suggestion of power tells the reader exactly what to look for. This sense of power grows throughout the novel, as Louise’s mental health continues to decline.

Louise works in the wings, discreet and powerful. She is the one who controls the transparent wires without which the magic cannot occur. She is Vishnu, the nurturing divinity, jealous and protective; the she-wolf at whose breast they drink, the infallible source of their family happiness. You look at her and you do not see her. Her presence is intimate but never familiar. (53)

Louise is both invisible and indispensable, a combination so powerful that you hardly notice her overtaking until it is too late. This is a power that Louise later flexes when Myriam and Paul try to put distance between the nanny and their family. Louise makes absolute certain that they know who is in charge now.

Louise’s power is initially tested when she is out of work with the flu for several days. Upon her return, Slimani writes,

at 7:30 a.m., she opens the front door of the apartment on Rue d’Hauteville. Mila, in her blue pajamas, runs at the nanny and jumps into her arms. She says: ‘Louise, it’s you! You came back!’ In his mother’s arms, Adam struggles. He has heard Louise’s voice, he has recognized her smell of talc, the light sound of her footsteps on the wooden floor. With his little hands, he pushes himself away from his mother’s chest. Smiling, Myriam hands her child into Louise’s loving arms. (156–7).

This is really where we see a shift in power between Myriam and Louise. The image of Myriam handing her children over, into Louise’s arms serves as a moment of foreshadowing for the complete control that Louise eventually maintains over the children and then concretes by taking their lives.

From this moment forward, Louise begins to take liberties with the children and flex her power in a way that is not prevalent in the first half of the book, and each time she takes another step forward, Myriam takes a step back, giving up control to this new mother who has taken over. Myriam starts to fear Louise, she acknowledges this power the nanny has and feels helpless against it.

But Louise has the keys to their apartment; she knows everything; she has embedded herself so deeply in their lives that it now seems impossible to remove her. They will drive her away and she’ll come back. They’ll say their goodbyes and she’ll knock at the door, she’ll come in anyway; she’ll threaten them, like a wounded lover. (175)

Louise’s power comes to a climax with a chicken carcass.

Myriam is about to open the fridge when she sees it. There, in the middle of the little table where the children and their nanny eat. A chicken carcass sits on a plate. A glistening carcass, without the smallest scrap of flesh hanging from its bones, not the faintest trace of meat. It looks as if it’s been gnawed clean by a vulture or a stubborn, meticulous insect. . . . Its thighs have been torn off, but its twisted little wings are still there, the joints distended, close to breaking point. . . . Louise can’t have done this by mistake or out of forgetfulness. And certainly not as a joke. No, the carcass smells of washing liquid and sweet almond. Louise washed it in the sink; she cleaned it and put it there as an act of vengeance, like a baleful totem. (162)

This peak of power also comes with the climax of Slimani’s novel. This is the closest to the murder scene that the reader is allowed. It is the first time we see Louise’s deliberate, evil, diabolical mind at work. Up until this point, Slimani has granted the reader hints at Louise’s darkness, but never allowed us the full picture. Here, with the chicken carcass, we get it. This scene serves as the pinnacle of tension between Myriam and Louise. These two mothers have been battling for power over this family throughout the novel, and now, Louise takes complete control in an ultimately feminine and violent act. Louise utilizes her power over the cleanliness of Myriam’s house, and over her children, to parade her control in front of Myriam. An integral moment of foreshadowing, Slimani’s presentation of this scene is in many ways, more haunting than the murder scene that she opens her novel with. The horror of a cleaned and washed chicken carcass lives in its clarity. Unlike the murders, where the reader would need the interiority with Louise to truly understand their purpose, Slimani is brutal in her delivery of Louise’s diabolical chicken threat, she “nurses a sordid hatred for her employers, an appetite for vengeance” (170). The reader understands, at this point more than any other time in the book, what Louise is capable of. This scene serves as a small piece of the reader’s search for why.

Despite an overarching lack of violence in Slimani’s novel, the author does hint at it immensely, and occasionally gives her readers violence in different circumstances outside of her murder of Mila and Adam. Biting and bite marks are a reoccurring theme and source of violence in the novel. Biting first presents itself when Mila runs off in the park one day.

Louise is about to put the child down when she feels a terrible pain in her shoulder. She screams and tries to shove the little girl away from her. Mila is biting her. Her teeth are sunk in Louise’s flesh, tearing it, drawing blood, and she clings to Louise’s arm like a rabid animal. (92)

When first reading this scene, the reader considers what an ill-behaved child Mila is and what a nasty thing to do this is. However, later in the novel, this perception shifts.

As she [Myriam] was undressing him, she noticed two strange marks, on his arm and at the top of his back. Two red scars, almost vanished, but where she can still make out what look like tooth marks. (119)

Louise tells Myriam that Mila was the one who bit baby Adam but there is considerable suspicion arising in both Myriam and the reader at this point.

Finally, we meet Hector, another child that Louise previously nannied for many years. He recalls “the strange way she had of kissing him, sometimes using her teeth, biting him as if to signify the sudden savagery of her love, her desire to completely possess him” (164). As the pieces come together, the gruesomeness of the biting becomes clear. Mila bites, because Louise bites, and has bitten children in the past. The biting is a morsel of foreshadowing and acts as a placeholder for a piece of the violence that we do not get in Louise’s final act. Here, things begin to unravel. The reader starts to understand Louise and her evilness less than we have in other parts of the novel.

The chapter ends:

He [Hector] realizes that what he first felt earlier, when the Police woman told them, was not shock or surprise but an immense and painful relief. A feeling of jubilation, even. As if he’d always known that some menace had hung over him, a pale, sulfurous, unspeakable menace. A menace that he alone, with his child’s eyes and heart, was capable of perceiving. Fate had decreed that the calamity would strike elsewhere. The captain had seemed to understand him. Earlier she had examined his impassive face and she had smiled at him. The way you smile at survivors. (167–168)

Louise is the ever-present evil. The other major source of violence Slimani includes in her novel occurs between Louise and her own daughter, Stephanie.

She opened the small front door. Barely had she closed it behind them then she started showering Stephanie with blows. She hit her on the back to start with, heavy punches that threw her daughter to the floor. The teenager curled up in a ball and cried out. Louise kept hitting her. She summoned all her colossal strength. Again, and again her tiny hands slapped Stephanie’s face. She tore her hair and pulled apart the girl’s arms, uncovering her head. She hit her in the eyes. She insulted her. She scratched her until she bled. When Stephanie didn’t move anymore, Louise spat in her face. (181)

This scene is by far the clearest example of violence Slimani writes into The Perfect Nanny. It shows her readers, much like the chicken carcass, what Louise is capable of. Although we get almost no violence towards the two children, Mila and Adam, until their death, we see in other aspects of Louise’s life and history that she is in fact capable of this level of treachery. This brutal act of violence against her own child clearly illustrates Louise’s capacity to inflict pain on those around her, even though she continues to come across as a doll-like, childish, small-handed, perfect blonde. This scene is another aspect of the why present in Slimani’s fairy-tale-gone-wrong.

Louise, and in her character analysis, the examination of Slimani’s foreshadowing, is perfectly bookended in the novel. The last time the reader sees Louise, Slimani writes,

She [Louise] has to admit that she no longer knows how to love. All the tenderness has been squeezed from her heart. Her hands have nothing left to caress. I’ll be punished for that, she hears herself think, I’ll be punished for not knowing how to love. (214)

The first time the reader sees Louise, “she didn’t know how to die. She only knew how to give death” (2). Louise does not know how to love, she only knows how to give death. This is the clearest juxtaposition and explanation that Slimani grants us in her work. The author takes her 228 pages of hints, and suggestions, and foreshadowing, and sums it up in this pristine parallel that lies on either end of her award-winning novel.

The veil between love and violence is slim—both powerful emotions driven by passion and all-encompassing when allowed. I wish I could say Louise felt completely foreign, that her slow descent into madness perplexed me. But the character’s struggle to regain control in a world that had stripped her powerless resonates with me. There is a mental aspect to abuse that weaves itself into you and refuses to let go, even long after the violence has left. There is a toll to being told that you are loved, and being hurt all at once. It tangles everything together. Laying on a wood floor, watching my blood fall, I told myself it was my fault—that this was my punishment for not knowing how to love.

SOFIA GRADY shoots tequila, likes to dance, and perpetually has somewhere she should have been twenty minutes ago. She graduated from Emerson College with a Master of Fine Arts in Nonfiction Writing in the winter of 2023. In her work, Sofia strives for uncomfortable vulnerability—to place emotions on the page not often expressed, in hopes of inspiring audiences to do the same. Currently, she works as a fitness instructor in Boston, Massachusetts.